Intermittent Fasting

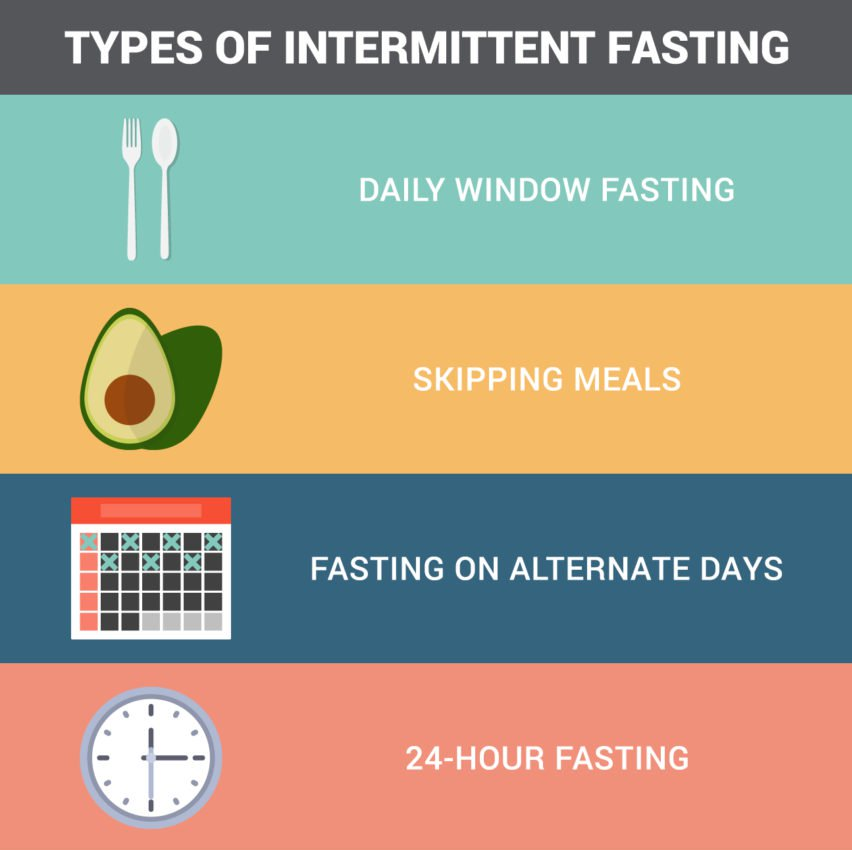

Intermittent Fasting refers to a group of dietary strategies that involve a period of fasting followed by a limited period of feeding. This can take multiple forms:

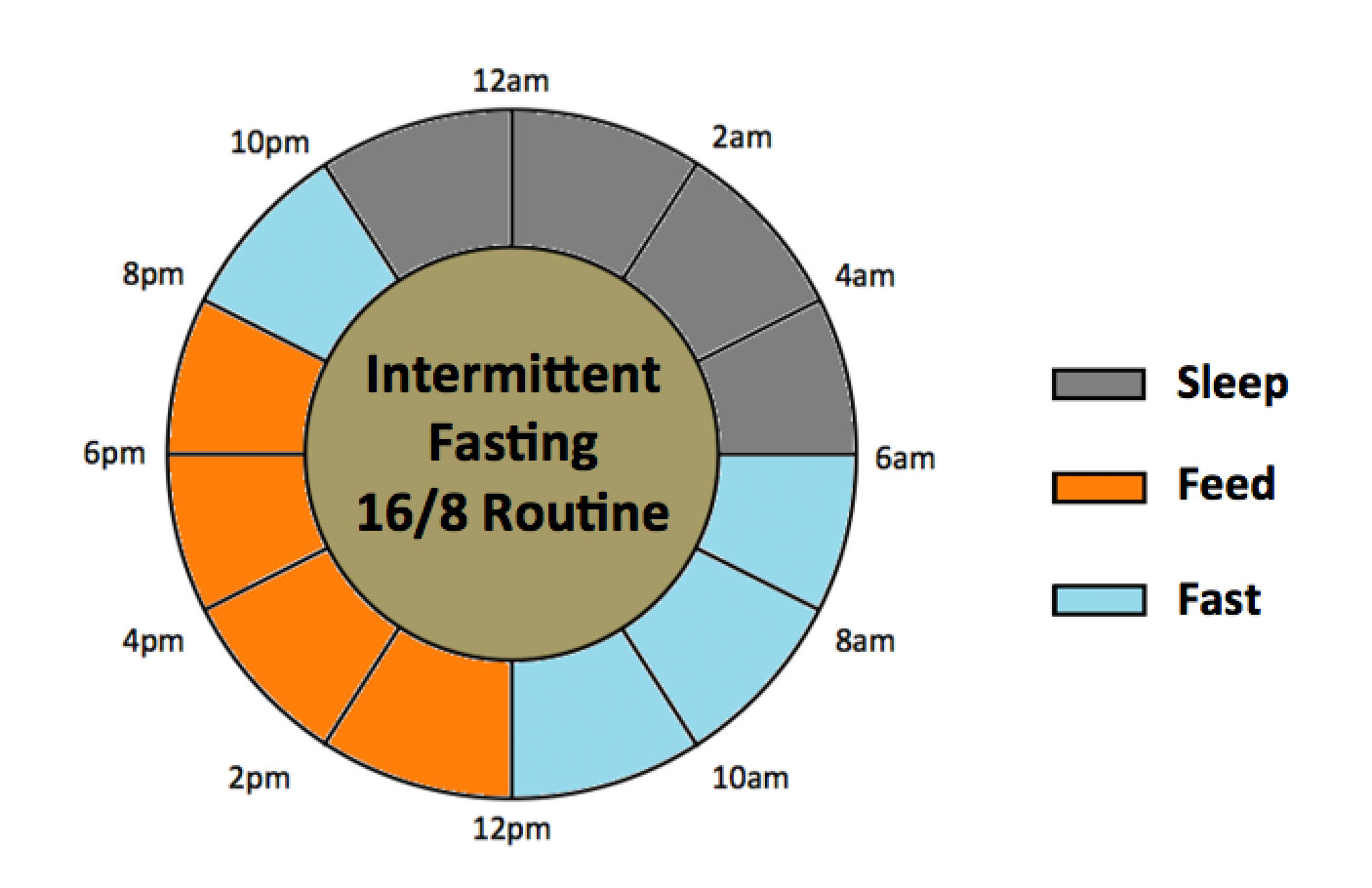

The most common form utilized for weight-loss is “daily window fasting” (also known as 16:8 fasting). “16:8” refers to a 16 hour period of fasting followed by an 8 hour feeding window that is a common schedule for those practicing this method. Since we are focused on intermittent fasting for physical fitness (rather than say for religious reasons such as Ramadan), when the term intermittent fasting (IF) is used in this article, one can assume it is referring to daily window fasting unless otherwise noted. It is prudent to note that much of the research presented is relevant for all forms of fasting as far as an athlete is concerned.

Summary

I do not recommend methods such as “alternate day fasting”, “skipping meals”, or “24 hour fasting” for an athlete under any circumstance. It has been shown that “muscle contraction during exercise, whether resistive or endurance in nature, has profound affects on muscle protein turnover that can persist for up to 72 hours. It is well established that feeding during the post-exercise period is required to bring about a positive net protein balance (muscle protein synthesis – muscle protein breakdown).”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19036897

Therefore, it would be smart for both those trying to lose fat and for those trying to gain muscle to meet daily protein requirements, especially on recovery days. This, along with liver glycogen depletion, precludes the use of other forms of IF except for “daily window fasting” for the serious athlete.

Practically, IF is a dietary strategy that can be used effectively for fat loss. It provides no significant fat loss advantage when compared to a continuous hypocaloric diet. It is simply a way for some individuals to control their daily caloric intake when adherence is an issue with standard methods. Acute hormonal changes (along with insulin and blood sugar alterations) are likely insignificant, and significant improvements in longevity markers also don’t appear to be any different when compared to a continuous hypocaloric diet…in other words it appears that fat loss is what leads to true health benefits, not the fasting itself.

A specific example of the aforementioned acute hormone effects is growth hormone (GH) increasing during fasting. This is a means for your body to protect its muscle stores. The main role of GH is to be anti-catabolic. During fasting, any increase in GH still remains within normal levels and growth hormone does not cause a significant change in muscle mass within these levels. This transient change may be heralded by IF gurus as a benefit without realizing that 1) it is inconsequential and 2) GH’s anabolic effect is largely limited to non-muscle tissues. Not only that, IGF-1 decreases when fasting. The “pro-hormonal” stance is simply misunderstanding what is happening. Growth hormone increase is a compensatory mechanism to “starvation”. Additionally: lower inflammation, improved immune function, improved cognitive function, and increased autophagy are all likely associated with the hypocaloric condition, rather than the fasting itself.

Proponents of IF may reference the MATADOR study that came to the conclusion: “Greater weight and fat loss was achieved with intermittent energy restriction (ER). Interrupting ER with energy balance ‘rest periods’ may reduce compensatory metabolic responses and, in turn, improve weight loss efficiency.” (Byrne et al 2018) However, their proposed mechanism “attenuation of adaptive thermogenesis” is not consistent with the data. The likely mechanism at play was better dietary adherence in the IF group. Consistent adherence to a caloric deficit is the number one factor in a weight-loss regimen.

There is no inherent magic (regardless of what gurus may claim) in using IF for fat loss. IF may be sub-optimal when attempting to gain muscle/strength or when performance is a goal, especially for elite athletes, if for no other reason than difficulty consuming an adequate amount of food during the feeding window.

Additionally, lean mass may be better preserved with a standard continuous diet in elite athletes undergoing extreme diet conditions. These effects may be less pronounced in recreational lifters as suggested by Tinsley et al. 2019, and therefore dietary protocol in recreational lifters should be chosen based on what will yield the greatest adherence.

Intermittent fasting should potentially be avoided by those with altered glycemic control, such as diabetics. As long as you understand these issues, IF can be used effectively to control your daily caloric intake, although performance may be affected for some.

Ultimately, when structuring a diet, refer to the Triangle:

Research

“We conducted a systematic review to examine the effect of overnight-fasted versus fed exercise on weight loss and body composition. Seven electronic databases were searched using terms related to fasting and exercise. Inclusion criteria were: randomised and non-randomised comparative studies; published in English; included healthy adults; compared exercise following an overnight fast to exercise in a fed state; used a standardized pre-exercise meal for the fed condition; and measured body mass and/or body composition. A total of five studies were included involving 96 participants. Intra-group analysis for the effect of fasted and fed aerobic exercise revealed trivial to small effect sizes on body mass. The inter-group effect for the interventions on body mass was trivial. Intra-group effects were small for % body fat and trivial for lean mass in females, with trivial effects also found for the inter-groups analyses.”

https://www.mdpi.com/2411-5142/2/4/43

“This systematic review in obese and overweight individuals showed that regular intermittent dieting decreased lean mass compared to continuous dieting. There were no differences in effects for either intermittent vs continuous interventions across all other outcomes. In contrast to previous systematic reviews, this study suggested that lean mass is better preserved in continuous dieting compared to regular intermittent dieting.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30206335

This study followed otherwise healthy adults over a one year period. Participants were 332 overweight and obese adults, ages 18-72 years. “The two forms of intermittent energy restriction (5:2 or alternate week) were not statistically different for weight loss, body composition, and cardiometabolic risk factors compared to continuous energy restriction.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30470804/

“Intermittent energy restriction is an effective alternative diet strategy for the reduction of HbA1c and is comparable with continuous energy restriction in patients with type 2 diabetes.” This is not surprising. Insulin levels will never supersede calorie levels where fat loss is concerned. During a caloric deficit, lower insulin levels are expected.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2688344

“IF, in the form of TRF, did not attenuate RT adaptations in resistance-trained females. Similar FFM accretion, skeletal muscle hypertrophy, and muscular performance improvements can be achieved with dramatically different feeding programs that contain similar energy and protein content during RT. Supplemental HMB during fasting periods of TRF did not definitively improve outcomes.”

https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/advance-article/doi/10.1093/ajcn/nqz126/5527779

“Both intermittent and continuous energy restriction resulted in similar weight loss, maintenance and improvements in cardiovascular risk factors after one year. However, feelings of hunger may be more pronounced during intermittent energy restriction.”

https://www.nmcd-journal.com/article/S0939-4753(18)30100-5/

“The study on lemurs and one of the two studies on macaques have reported a lifespan increase. In this review, I argue that these results are better explained by a lifespan decrease in the control group because of a bad diet and/or overfeeding, rather than by a real lifespan increase in calorie‐restricted animals. If these results can be readily translated to humans, it would mean that no beneficial effect of calorie restriction on lifespan can be expected in normal‐weight or lean people, but that overweight and/or obese people could benefit to some extent from a decrease in excessive food intake.”

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/bies.201800111

This meta showed: “While intermittent fasting appears to produce similar effects to continuous energy restriction to reduce body weight, fat mass, fat-free mass and improve glucose homeostasis, and may reduce appetite, it does not appear to attenuate other adaptive responses to energy restriction or improve weight loss efficiency. Intermittent fasting thus represents a valid–albeit apparently not superior–option to continuous energy restriction for weight loss.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26384657

This meta showed: “Blood lipid concentrations, glucose, and insulin were not altered by intermittent energy expenditure in values greater than those seen with continuous energy restriction.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27338458

This meta showed: “Intermittent energy restriction may be an effective strategy for the treatment of overweight and obesity. Intermittent energy restriction was comparable to continuous energy restriction for short term weight loss in overweight and obese adults.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/29419624/

“Both groups showed a significant loss of weight and fat mass from baseline, but no significant between-group differences were noted in any outcome measure. These findings indicate that body composition changes associated with aerobic exercise in conjunction with a hypocaloric diet are similar regardless whether or not an individual is fasted prior to training.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4242477/

“Our results on the effects of the “5:2 diet” indicate that Intermittent calorie restriction may be equivalent but not superior to continuous calorie restriction for weight reduction and prevention of metabolic diseases.”

https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article-abstract/108/5/933/5201451

Intermittent Fasting may cause some negative health outcomes in certain populations. People with altered glycemic control should avoid fasting, as it causes poorer glucose response.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26220945

Both intermittent and continuous energy restriction achieved a comparable effect in promoting weight-loss and metabolic improvements.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30583725

Men and women with obesity had more favorable changes in nutritional composition and eating behavior with continuous energy restriction than intermittent fasting.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41430-018-0370-0

“Alternate-day fasting and standard daily calorie restriction similarly improve the FFM:total mass ratio and reduce leptin after a 24-wk intervention.”

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261561417314164