Ketogenic Diet: Body Composition and Health

Summary:

According to the JISSN (2017): “Ketosis is a condition attained by restricting carbohydrate to a maximum of ~50 g or ~10% of total energy [45], while keeping protein moderate (1.2–1.5 g/kg/d) [49], with the remaining predominance of energy intake from fat (~60–80% or more, depending on degree protein and carbohydrate displacement). A ketogenic diet can raise circulating ketone levels to a range of ~0.5–3 mmol/l, with physiological ketosis levels reaching a maximum of 7–8 mmol/l [49].”

Keto is popular due to the apparent rapid weightloss seen in the first month. Note the term “weightloss”. The majority of the weight that a person initially sheds is a combination of water and muscle glycogen, not body fat. This gives the illusion of rapid results.

The ketogenic diet has quite varied outcomes in regard to body composition in the research overall. The main theme appears to be that it is likely not optimal for hypertrophy long-term (carbs support needed energy and recovery functions, very high muscle glycogen storage and the avoidance of low to moderate states may improve anabolic signalling to muscle tissue, glycogen mediated recovery, generally lower cortisol levels, and various other benefits), it is equivalent to other diets with regard to fat loss when protein and calories are controlled, and it potentially hinders many performance modalities. It is possible future studies may elucidate routines where tailored carb placement (in the absence of moderate to intense cardio) around workouts could attenuate some of the negatives related to Keto and hypertrophy/strength development, however this technique is currently speculative.

A ketogenic diet yields similar, but not superior, fat loss results to other dietary strategies when calories and protein are controlled. Metabolic ward studies routinely show similar results in body composition when comparing keto to a standard continuous diet for fat loss purposes. Controlled interventions to date that matched protein and energy intake between keto and non-keto conditions have failed to show a fat loss advantage (JISSN 2017). Many low carb/keto studies over-estimate their effect on burning calories due to a common methodology error. Doubly labeled water calculations failing to account for diet-specific energy imbalance effects on respiratory quotient erroneously suggest that low-carbohydrate diets substantially increase energy expenditure (Hall 2019). When this error is corrected, Keto has not been shown to be superior for fat loss.

Keto may be a viable option for fat loss in a hypocaloric state where performance is not a concern in otherwise healthy individuals (and may confer some appetite blunting effects). Ketosis is entered after ~48 hours according to Sumithran and Proietto (2008). According to Hall et al (2016), keto-adaptation takes ~7-10 days. This is based on maximization of the rates of adipose lipolysis, hepatic ketogenesis, and whole body daily fat oxidation. The rise in fat oxidation, measured via decreased respiratory quotient, plateaus within the first week. Thus, this is the currently accepted scientific keto-adaptation period. According to keto proponents, it can take anywhere from months to multiple years (although this is not based on any formally objective measure).

Glucose intolerance due to the down-regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase and decrease in glycogenolysis are potentially unwanted side effects of the ketogenic diet as is a potential increase in LDL-C, although the latter likely normalizes over time. While a short-term Ketogenic diet is associated with an improved fasting metabolic profile, longer term potentially exacerbates systemic glucose intolerance compared to a traditional Western-style high-fat diet. KD-associated glucose intolerance is most likely the result of increased liver glucose output rather than impaired glucose uptake by other tissues (Grandl et al, 2018).

Prurigo Pigmentosa is another potential serious, but rare, side effect of ketosis. PP is “characterized by the sudden onset of erythematous papules that leave a reticulated hyperpigmentation when they heal” ICD. Treatment consists of antibiotics and cessation of the ketogenic diet.

Ketogenic diet adaptation also comes with a host of potential mild to moderate side effects. Moreno et al compiled a list of observed side effects from their long-term very low carb or Keto (VLCK) diet vs low carb (LC) diet trial:

There is research on both sides of the aisle when comparing low fat to low carbohydrate diets suggesting superiority of one or the other. Adherence to any dietary regimen that promotes a caloric deficit will work for fat loss. A ketogenic diet may also serve a purpose in certain medical conditions such as epilepsy (among others), but is outside of the scope of this article and should be performed under the guidance of a qualified doctor or dietitian.

Ultimately, a standard continuous caloric deficit diet is likely the healthiest way to lose body fat for the majority of the population if for nothing else than less risk of adipogenicity from a high fat diet and less risk of nutrient deficiency from an exclusion diet such as keto (low fruit intake being one concern).

For a look at the research regarding Keto and performance, please refer to our Performance article.

Research:

A ketogenic diet for three weeks increased LDL-C with 44% versus controls. The individual response on LCHF varied profoundly.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30408717

The isocaloric keto diet was not accompanied by increased body fat loss compared to a standard diet but was associated with relatively small increases in energy expenditure that was near the limits of detection with the use of state-of-the-art technology.

https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/104/2/324/4564649

Ketogenic diets and Non Keto low carb diets were equally effective in reducing body weight and insulin resistance, but the Ketogenic diet was associated with several adverse metabolic and emotional effects. The use of ketogenic diets for weight loss is not warranted.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16685046

Reduced-calorie diets result in clinically meaningful weight loss regardless of which macronutrients they emphasize.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19246357

In this 12-month weight loss diet study, there was no significant difference in weight change between a healthy low-fat diet vs a healthy low-carbohydrate diet

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29466592

The carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity theorizes that diets high in carbohydrate are particularly fattening due to their propensity to elevate insulin secretion. Insulin directs the partitioning of energy toward storage as fat in adipose tissue and away from oxidation by metabolically active tissues and purportedly results in a perceived state of cellular internal starvation. In response, hunger and appetite increases and metabolism is suppressed, thereby promoting the positive energy balance associated with the development of obesity. Several logical consequences of this carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity were recently investigated in a pair of carefully controlled inpatient feeding studies whose results failed to support key model predictions. Therefore, important aspects of carbohydrate-insulin model have been experimentally falsified suggesting that the model is too simplistic.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28074888

Low-fat diet (LFD) + progressive resistance exercise (PRE), carbohydrate-restricted diet (CRD), and CRD + PRE preserve fat free mass similarly. PRE is an important component of a low fat diet during weight loss

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22283635

Doubly labeled water (DLW) calculations failing to account for diet-specific energy imbalance effects on respiratory quotient erroneously suggest that low-carbohydrate diets substantially increase energy expenditure.

https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/109/5/1328/5480991

The low-carbohydrate diet was more effective for weight loss and cardiovascular risk factor reduction than the low-fat diet. Restricting carbohydrate may be an option for persons seeking to lose weight and reduce cardiovascular risk factors.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25178568

We detected a mildly negative impact from this 6-week non-energy-restricted KD on physical performance (endurance capacity, peak power and faster exhaustion). Our findings lead us to assume that a KD does not impact physical fitness in a clinically relevant manner that would impair activities of daily living and aerobic training. However, a KD may be a matter of concern in competitive athletes.

https://nutritionandmetabolism.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12986-017-0175-5

21-days of a ketogenic diet did not impair nutritional state; did not cause negative changes in global measurements of nutritional state including sarcopenia, bone mineral content, hepatic, renal and lipid profile.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28537652

This study showed that independently of the method for weight loss, the negative energy balance alone is responsible for weight reduction.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18025815

Evidence from this systematic review demonstrates that low-carbohydrate/high-protein diets are more effective at 6 months and are as effective, if not more, as low-fat diets in reducing weight and cardiovascular disease risk up to 1 year. More evidence and longer-term studies are needed to assess the long-term cardiovascular benefits from the weight loss achieved using these diets. Unfortunately they did not focus on isocaloric studies and the results are likely due to increased protein intake in the low carb group.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18700873

Trials show weight loss in the short-term irrespective of whether the diet is low carb (CHO) or balanced. There is probably little or no difference in weight loss and changes in cardiovascular risk factors up to two years of follow-up when overweight and obese adults, with or without type 2 diabetes, are randomised to low CHO diets and isoenergetic balanced weight loss diets.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25007189

Resistance exercise in combination with a ketogenic diet may reduce body fat without significantly changing LBM, while resistance exercise on a regular diet may increase LBM without significantly affecting fat mass. Fasting blood lipids do not seem to be negatively influenced by the combination of resistance exercise and a low carbohydrate diet.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20196854

This trial-level meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing Low CHO diets with Low FAT diets in strictly adherent populations demonstrates that each diet was associated with significant weight loss and reduction in predicted risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events. However, LoCHO diet was associated with modest improvements in weight loss and predicted ASCVD risk in studies from 8 weeks to 24 months in duration. These results suggest that future evaluations of dietary guidelines should consider low carbohydrate diets as effective and safe intervention for weight management in the overweight and obese, although long-term effects require further investigation.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26485706

These findings suggest that the long-term effect of low-fat diet intervention on bodyweight depends on the intensity of the intervention in the comparison group. When compared with dietary interventions of similar intensity, evidence from RCTs does not support low-fat diets over other dietary interventions for long-term weight loss. The key component appears to be a hypocaloric condition to promote weight-loss.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26527511

This meta-analysis demonstrates opposite change in two important cardiovascular risk factors on LC diets–greater weight loss and increased LDL-cholesterol. Our findings suggest that the beneficial changes of LC diets must be weighed against the possible detrimental effects of increased LDL-cholesterol.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26768850

A wide range of dietary approaches (low-fat to low-carbohydrate/ketogenic, and all points between) can be similarly effective for improving body composition.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26768850

“It has been postulated that the production and utilization of ketone bodies impart a unique metabolic state that, in theory, should outperform non-ketogenic conditions for the goal of fat loss [45]. However, this claim is largely based on research involving higher protein intakes in the LCD/KD groups. Even small differences in protein can result in significant advantages to the higher intake. A meta-analysis by Clifton et al. [52] found that a 5% or greater protein intake difference between diets at 12 months was associated with a threefold greater effect size for fat loss. Soenen et al. [53] systematically demonstrated that the higher protein content of low-carbohydrate diets, rather than their lower CHO content, was the crucial factor in promoting greater weight loss during controlled hypocaloric conditions. This is not too surprising, considering that protein is known to be the most satiating macronutrient [54]. A prime example of protein’s satiating effect is a study by Weigle et al. [55] showing that in ad libitum conditions, increasing protein intake from 15 to 30% of total energy resulted in a spontaneous drop in energy intake by 441 kcal/day. This led to a body weight decrease of 4.9 kg in 12 weeks. With scant exception [56], all controlled interventions to date that matched protein and energy intake between KD and non-KD conditions have failed to show a fat loss advantage of the KD [51, 53, 57, 58, 59, 60].”

https://jissn.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12970-017-0174-y

In this meta-analyses by Hall and Guo, which included only isocaloric, protein-matched controlled feeding studies where all food intake was provided to the subjects (as opposed to self-selected and self-reported intake). “No thermic or fat loss advantage was seen in the lower-CHO conditions. In fact, the opposite was revealed. Both energy expenditure (EE) and fat loss were slightly greater in the higher-CHO/lower-fat conditions (EE by 26 kcal/day, fat loss by 16 g/d); however, these differences were too small to be considered practically meaningful.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28193517

At endurance event (low) intensities: ergolytic effects from keto-adaptation appear to be accompanied by a reduction in exercise economy (increased oxygen demand for a given speed). The linear and non-linear high-CHO diets in the comparison both caused significant performance improvements, while no significant improvement was seen in the ketogenic diet (there was a non-significant performance decrease).

https://physoc.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1113/JP273230

While low-carbohydrate diets have been suggested to partially subvert these processes by increasing energy expenditure and promoting fat loss, our meta-analysis of 32 controlled feeding studies with isocaloric substitution of carbohydrate for fat found that both energy expenditure (26 kcal/d; P <.0001) and fat loss (16 g/d; P <.0001) were greater with lower fat diets.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28193517

Citation: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29986720

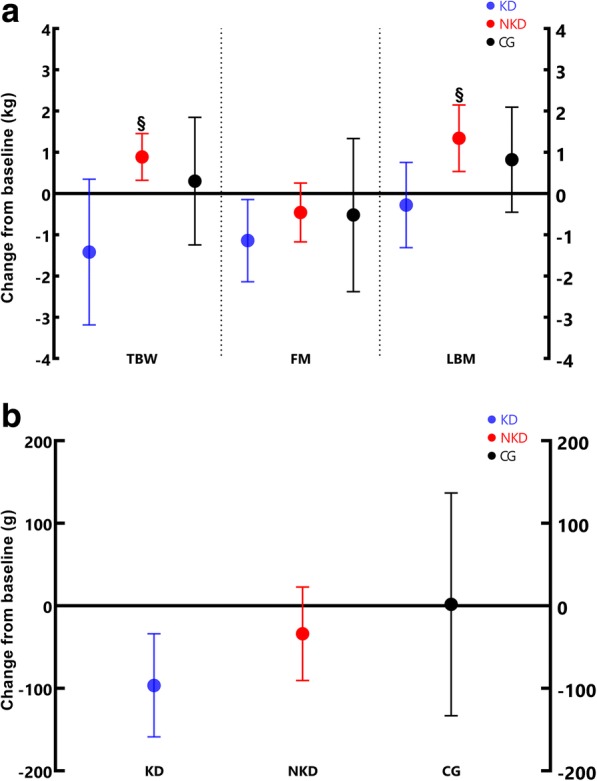

Legend: [a] Total body weight (TBW); Fat mass (FM); Lean body mass (LBM); [b] Visceral adipose tissue (VAT)